NDYUKA (AUKAN) PEOPLE: SURINAME`S MATRIARCHAL HARDWORKING MAROON TRIBE

The Ndyuka people, also known as Aukan people or Okanisi sama, are a Maroon Ndyuka creole-speaking ethnic group who live in the deep, interior of the rain forests of Eastern part of Suriname and french Guiana. As a result of their language and cultural similarities to Akan people of West Africa some historians include them among Akan people, after all they call themselves Aukan. The Ndyuka are subdivided into the opu, who live upstream of the Tapanahony River of southeastern Suriname, and the bilo, who live downstream of that river. They further subdivide themselves into fourteen matrilinear kinship groups called lo.

Dyuka people of Suriname

They are the descendants of African slaves brought over from Central and West Africa in the 17th and 18th centuries by the Dutch to work the many plantations in the coastal regions. Conditions on the plantations were often cruel and inhumane resulting in escapes of slaves into the jungle interior of the country where

they would not be followed. The Aukaners set up their own societies, forming a unique culture, language and lifestyle. For over 300 years the Aukaners have lived in relative isolation from the outside world. This paper will attempt to explore and document who the Aukaners are and provide at least an initial look into how they view the world.

Ndyuka woman and her baby girl

Classification/Name

Slaves who escaped from their captivity to form independent people groups are known as Maroons. There are two Maroon groups in Suriname: the Aukaners and the Saramacans. Aukaners go by two different names depending largely on the location in which they live. Those Aukaners who live along the Tapanahony River and make up the ethnographic core of the people group refer to themselves as Ndjuka. Aukaners who live in the city as well as the coastal Cottica River region refer to themselves simply as Aukaners.

Ndyuka tribes men of Suriname

While these two groups of individuals go by different names, they share the same cultural, historical and family background and see themselves as the same people group. There are two other related groups that speak a very similar dialect to Aukans: the Aluku, and the Paramacca. These two groups today are considered distinct. Of these the Aukan/ Ndjuka is the largest group, numbering approximately 33,000. In spite of the their common kinship and language, the Aukaner sub-groups are not friendly with each other and do not necessarily cooperate. Within the last few years, a large but undetermined number of Aukaners have migrated to French Guiana.

Ndyuka people

Language

Ndyuka also called Aukan, Okanisi, Ndyuka tongo, Aukaans, Businenge Tongo, Eastern Maroon Creole, or Nenge is a creole language of Suriname, spoken by the Ndyuka people. Most of the 25 to 30 thousand speakers live in the interior of the country, which is a part of the country covered with tropical rainforests. Ethnologue lists two related languages under the name Ndyuka.

Ndyuka is based on English vocabulary, with influence from African languages in its grammar and sounds. For example, the difference between na ("is") and ná ("isn't") is tone; words can start with consonants such as mb and ng, and some speakers use the consonants kp and gb. (For other Ndyuka speakers, these are pronounced kw and gw, respectively. For example, the word "to leave" is gwé or gbé, from English "go away".) There are also influences from Portuguese and other languages.

Slavery destroyed entire continent - On the hunt runaway slaves was opened with bloodhounds. Once caught, they could count on the death penalty. Following the English poem "The Dismal Swamp" by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Richard Ansdell painted in 1861 the hunted slave couple. - Photo National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside

Modern orthography differs from an older Dutch-based orthography in substituting u for oe and y for j. The digraphs ty and dy are pronounced somewhat like the English ch and j, respectively. Tone is infrequently written, though it is required for words such as ná ("isn't"). The Ndjuká syllabary was invented by Afaka Atumisi of eastern Suriname in 1910. Afaka claimed that he had a dream in which a spirit prophesied that a script would be revealed to him. He went on to invented the Ndjuká or Djuka script, which is also known as the Afaka script (afaka sikifi).

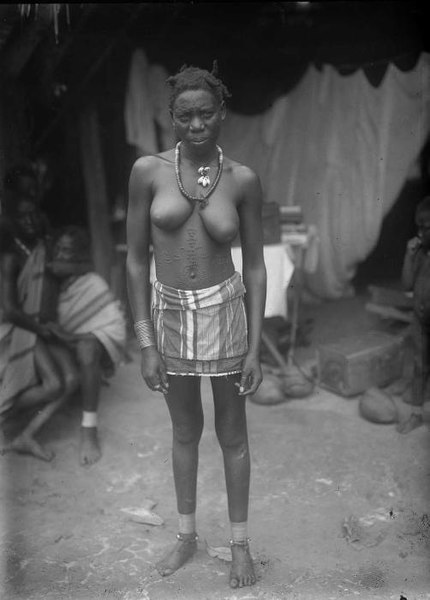

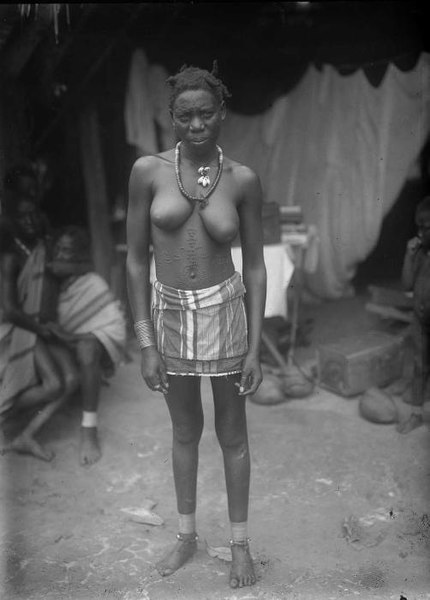

A Woman of Maroon Aukaanse (Ndyuka) descent. Her clothing consists of a pangi, worn to her waist and a cloth tied across her right shoulder.She also carries a number of rings above her ankle. Circa 1900

The Ndyuka language has three dialects: proper Ndyuka (or Okanisi), Aluku, and Paramaccan, which are ethnically distinct. Kwinti is distinct enough linguistically to be considered a separate language, though it too is sometimes included under the name Ndyuka.

Ndyuka was also a basis of the Ndyuka-Tiriyó Pidgin. Here is an example of Ndyuka text, and its translation into English (showing the similitarities as well as the lexical evolution), adapted from Languages of the Guianas (SIL Publications):

En so den be abaa na a líba, dísi wi kai Kawína Líba. Di den abaa de, den abaa teke gwe na opu fu Kawína. En so den be waka langa langa gwe te na Mama Ndyuka ede, pe wi kai Mama Ndyuka.

And so they crossed the river, which we call "Kawina [Commewijne] River". Having crossed it, they went way upstream along the Commewijne. Thus they walked a long, long way, clear to the upper Tapanahony, the place we call "Mama Ndyuka".

The language bears some similarity to Twi and other Akan languages spoken by the Akan people of Ghana.

Aukaners of Suriname

Brief History

The Aukaners were slaves who escaped from plantations on the coastal part of Suriname in the 1600’s and 1700’s. After their escape, these freed slaves would form clans, which are the building blocks of their society even today; villages were located in the jungle interior. In an effort to free other slaves, the Maroons frequently raided Dutch plantations resulting in loss of property and some loss of Dutch lives.

A protracted guerilla war ensued ending only with a peace treat with the Dutch in 1760. The Aukaners were the first of the Maroon groups to be granted semi-independence as a result of this treaty. The Aukaners were free to live in isolation and received annual payments from the Dutch government to cease their raiding of Dutch plantations.

The Aukaner people remained relatively isolated until the 1950’s when the government in Paramaribo began to employ Ndjuka’s. This pace of migration continued in the 60’s and 70’s as tens of thousands of Surinamers moved to the Netherlands in the wake of Suriname independence in 1975. (About 1/3 of the Suriname population –200,000 people – migrated to the Netherlands.)

In 1986 a Civil War began in Suriname between the Maroons and the Dutch government. As a result many of those who had migrated to the capital returned home to renew their cultural ties and re-establish their loyalties. The war lasted until 1990 when a new peace treat was finally signed. It is important to note that the war was responsible for a renewed commitment to their own way of life and culture for the Aukaner people.

Even though today up to 50% of the population at some time or another lives in the capital (of these, 25% are permanent moves and 25% are temporary, employment moves), they still consider themselves solidly Aukaner and are proud of their history and heritage.

The Ndjuka appear the most mobile and market-oriented of all Maroons. By the early 19th century, the Ndjuka had settled closer to the urban area, along the Cottica and Lower Saramaka Rivers. Ndjuka men marketed timber to Paramaribo customers and occasionally grew food for plantations along the coast and for Paramaribo (ThodenVanVelzen and VanWetering 1991). Since the 1960s many Ndjuka have moved to Paramaribo, primarily for economic reasons (Lamur 1965). Today, Maroons make up 4.6% of the larger Paramaribo area (Schalkwijk 1994: 22). Most urban Maroons seem to be of Ndjuka origin. If only half of the Maroons in Paramaribo are Ndjuka, then about 30% of the Ndjuka population live in the city today. The Ndjuka work more in mining than Maroons from other groups.

Late Paramount Chief of Ndyuka, Granman Matodja Gazon

Economy

Agriculture is the main focus of the Aukan economy. Items grown, however, are for the personal use of those who grow them (as well as a small group of related family members). There are no markets. The main crop is dry rice; other crops include cassava, taro, okra, maize, plantains, bananas, sugar cane and peanuts. Hunting and fishing are also significant contributors to the overall economy of the region. Again, game and fish are shared with a small group of kinsmen; none are purchased in a market-style economy.

Also contributing to the Aukan economy today are items purchased in Paramaribo by Aukan men employed there. These items are then brought into the interior and include shotguns, tools, pots, cloth, hammocks, salt, soap, kerosene, rum, outboard motors, transistor radios, and tape recorders. Aukaners are also emplyoyed in the areas of forestry and gold mining. Gold mining is now employing many Aukaners , especially in the are of Sella Creek (a tributary of the Tapanahoni).

Family Structure

The primary family unit in Aukan society is the matriclan (“lo”). Matriclans originated from a particular group of runaway slaves of a specific plantation from which they derived their names. There are twelve matriclans; each matriclan contains kinsmen who are matrilineally related. These are the strongest family ties; marriage is important but does not produce as vital a family link.

Each Aukan village contains three groups of people:

1.) matrilineal descendants of common ancestress (“people of the belly”)

2.) descendants of the men of the matrlineage (“fathers made them

children”)

3.) those who moved to these villages as relatives by marriage; i.e. affines(“those who have come to live”)

Aukaners practice polygamy (more than one wife for a man) but only if the man can afford to maintain more than one household. About 1/3 of the marriages are polygamous. Marriage in the Aukan sense consists of an official meeting held of the woman’s matriclan resulting in a verbal contract. Basically, the woman agrees to bear the man’s children; the man agrees to provide materially for his wife.

Once married couples must choose where they will live. Due to the fact that 1/3 of the men have more than one wife, care is taken in making that choice! In a recent study the following was discovered:

25% couples chose to live in the village of the husband’s family

30% couples chose to live in the village of the wife’s family

28% couples chose to live in both places

15% chose to live in their own villages with only brief visits to each other

It is not unusual for a man to own a house in his wife’s village, his lineage village and his father’s village. Divorce is relatively easy and frequent, some say as high as 40%. In order to obtain a divorce, the man informs his wife’s matriclan’s leaders that he no longer wants to be her husband. If the man has wronged the woman in some way, a fine is levied by the matriclan to appease the ancestral spirits. It is said that if a woman “overpowers” a man by her attitudes and actions that man should divorce his wife and go back to his own village

Neighbor/Village Relationships

There are many family groups within each village in Aukan society. Families relate to each other on a competitive basis. Limited resources, game, fish and planting grounds lead to a competitive agenda. Most family to family meetings take place to settle disputes between the families. Friendships are few outside of the family.

Aukan society is egalitarian; no social classes exist for the most part. There are positions of respect, however. The hierarchy of respect for most Aukan villages is as follows: religious practitioner followed by gaanman followed by captains followed by basias followed by storeowners/teachers followed by matriclan leaders.

There is also a hierarchy in terms of levels of trust for an Aukaner. The following shows who an Aukaner would trust and in what order: Fellow villagers followed by Fellow clan members followed by Whole Aukan linguistic/cultural group followed by Fellow Maroons followed by Fellow Surinamers followed by Foreigners (white people – bakaa).

There is also a hierarchy in terms of levels of trust for an Aukaner. The following shows who an Aukaner would trust and in what order: Fellow villagers followed by Fellow clan members followed by Whole Aukan linguistic/cultural group followed by Fellow Maroons followed by Fellow Surinamers followed by Foreigners (white people – bakaa).

Aukaner selling stuffs at Paramaribo,Suriname

As can be seen, any white person or non-Aukaner is looked at with a certain level of distrust. Aukaners must always see themselves as being in the winning position when dealing with foreigners. They are very hesitant to reveal their true thoughts to foreigners, especially in the areas of religion and folk tales. This has obvious ramifications for the missionary, and every effort must be made to gain trust and acceptance.

Ndyuka tribe Maroons of Suriname oerforming their traditional dance

The Authority/Political Structure

There are four groups of authority in Aukan society: elders (including the paramount chieftain – the Gaanman); the captains (kabitens); kunu (avenging spirits of ancestors); and the priests (shamans, herbalists, funeral foremen, etc.). The elders make most of the decisions that are non-religious in nature in the society. Captains are local leaders; the primary captain (like a mayor in some sense) is called the Ede Kabiten. Each

captain as two male and two female assistants called basias. Male basias act as village criers, announcing the beginning of village functions as well as other news. Female basias cook and serve food for large village functions and maintain mortuary and other meeting places. In reality priests have the utmost authority in that they interpret the wishes of ancestral spirits and kunu. More detail on this will be provided in the section

on religion.

The principal political offices (Gaanman and kabitens) are determined through matrilineal lines. Successors of these offices are distant relatives (must belong to the next generation) of the preceding officer.

Beautiful painting of Aukaner people

Law and Order (Social control)

Religious taboos form the framework of law and order in the Aukan society. When a dispute arises among Aukaners, it is usually settled after an impasse is reached. Typically, there is much yelling and gesticulating. A mediator (who is usually an affine; i.e. one who has married into the family) is called in to keep grievance from escalating to the point of angering the matriclan’s ancestors.

Ndyuka people

In settling disputes, both sides must feel that they have achieved a cumulative gain in the decision-making process. The fear of kunu generally acts as a strong motivation to settle the dispute. If the kunu become angry, there will be sickness and/or death in some member of the village (not necessarily the disputing parties). As a result, it is in the best interest of the entire village to make sure that disputes are settled before matters escalate.

Physical abuse is uncommon; striking each other is a very strong taboo. The exception to this rule is a wife caught in adultery – in this instance the husband has the right to beat the wife within certain parameters. (He must not use a stick or other weapon; the fight cannot take place on river or in the fields.) Citizens in this case are expected to intervene and stop punishment (much like the intervention of adults in the discipline of

children). Unfortunately, in recent times there have been higher levels of physical abuse, perhaps resulting from the negative influence of gold miners in the area.If a member of a village refuses to settle a dispute, the common punishment is ostracism. It is important to realize, however, that the overarching theme of Aukan law is a pursuit of mercy over justice. If, however, the ancestral spirits demand justice, punishment is carried out swiftly out of fear.

Nduka people

Religious Structure

Religion plays an extremely important role in the life of the Aukaner. The religious structure is one of animism and ancestral spirit veneration. There is a three tiered hierarchy of gods which plays a crucial role in every aspect of Aukan life. Some of the most significant gods are now discussed. The creator, the god who is

most powerful, is called “masaa gadu.” One of the most powerful spirits is “father god” (“papa gadu”) which is an incarnation of the boa constrictor. This is a god of mayhem and evil and is invoked in witchcraft. Because Aukaners are polytheistic, they are often willing to add Jesus to their pantheon of gods, probably in the second tier.

Superstition plays a major role in the life of an Aukaner. Individuals live in fear that they will commit some sin that will upset their ancestral spirits. Avenging, ancestral spirits are called “kunu” and must be appeased (through libations and sacrifices) when a wrong is committed. All sickness (especially serious illness) is seen to be the result of kunu action. In sickness or death, the ritual of divining is undertaken to determine the

cause of the illness (i.e., who is to blame for the sickness by their sin). This is accomplished through the use of oracles (often hair of the deceased) tied in a bundle and attached to a long plank. Two men hold the plank on their heads and then questions are put to the oracle. The way the plank moves, answers the questions. Aukaners also use charms, amulets, and fetishes to protect them from evil. Witchcraft is a reality in the Aukan society and is to be feared. Priests make decisions on whether someone is a witch. Frequently, when someone dies of unknown reason, the priest will mark them as a witch.There is a definite sense of good and evil in the Aukan mind set. Evil is associated with great danger, so it is to be avoided as much as possible. When a sin is committed, atonement is made quickly as directed by religious practitioners (priests and

mediums). The concept of salvation by faith is foreign to Aukan thinking. There is the concept of mercy in their system of justice, but atonement must always be made to cover sin. Aukan mindset would be equivalent to a salvation by works. Converts to any religion (including Christianity) are seen as a definite threat to the Aukan way of life. Often, new converts move out of their houses into new homes away from the traditional

village. Aukaners will intially listen to converts and try to add this new belief into their own religious world view. Syncretism is a real possibility and steps must be taken to ensure that true Christianity is presented.

The Aukaner sees God as stern, far-removed and a deity to be feared. The belief is that God became disgusted with mankind (especially the Aukan people) and removed himself from their presence. Prayers center around pleas for mercy for any accidental sins they may have committed.

Religious leaders hold an important place in society and have a great amount of power. Often the spiritual leaders are chosen by the ghost of a deceased ancestor or one of the gods to be used as a medium. The individual will then become possessed to give a message to the matriclan. The more this individual is possessed, the more of a spiritual leader he becomes. Eventually, after years of serving his clan as a medium, the person will be elevated to the position of priest. It is significant to note here that men alone can be possessed by the most important spirits. Women do act as mediums of the snake gods.

Ancestral shrines are important to Aukan ritual life, and, in fact, must be present for a settlement to be a true Aukan village. The two ancestral shrines of most significance are the mortuary (“Kee Osu”) and the ancestor pole/flagpole (“Faakatiki”).As stated earlier, Aukaners are mistrustful of foreigners and resistant to true

Christianity. They are a strong-willed people who are very proud of their heritage. They are especially proud to be the descendants of runaway slaves whom they see as their brave and defiant ancestors. Acceptance of Christianity, in the Aukan mind, would involve turning away from their ancestors and rejecting their way of life. Pentecostal churches have made some breakthroughs in Aukan society. It is estimated that there are

about 3000 Aukan Christians, the majority of whom live in Paramaribo or the Cottica region. Worship is led in Sranan Tongo. There are very few Christians in the interior

Ndjuka God Pantheon

Three Tiers

I MASAA GADU - The Lord God

-The fountainhead of all Creation

FOR ALL HUMANKIND

II GAAN Gadu-Great God or OGII-Danger GEDEONSU-Protector

GAAN Tata-Great Father

-Defender against Ndjuka enemies -King of forest Sprits -Shielding,comforting deity

such as witches “Wisimen” -Ambivalent toward humans -Offers solace

-Led Ndjukas out of slavery -Very Destructive unless appeased -Medicine Men “Obiaman”

-Defends traditional values/culture

assoc. with this deity

(taboos & persecutes thieves, immoral)

THESE ARE TRIBAL / NATIONAL GODS OF AUKANERS

III Yooka Papa Gadu or Vadu Ampuka Kumanti

Ancestor Spirits Reptile Spirits Bush Spirits Celestial Spirits

Birds, thunder/lightning

Bakuu – Demon Spirits

Helpful then turn destructive

-Depicted as humans with special powers

-Control particular domains and have particular interests and frailties

-Are able to procreate

-Except for Kumanti, all can turn into Avenging Spirits (Kunu)

THESE ARE MINOR DEITIES OR INVADING SPIRITS

Religious Bridges

There are many bridges to the gospel in the Aukan religion. Bridges identified

thus far include the following:

Belief in mercy and merciful intervention

Belief that God is the creator

Belief in sin

Belief in sacrifice to make atonement

Concept of “You reap what you sow.”

Concept of ancestors – presenting Old Testament characters as ancestors of faith (one specific story – Joseph)

Belief in the after life

No trouble believing Jesus did miracles and was son of God

Belief in the spiritual world

These bridges can be used as points of agreement in sharing the Gospel of Jesus Christ .

Dress

The Aukan people have a very typical style of dress which distinguishes them from Western society. Aukan women often go topless or wear a bra only. The upper thigh, buttocks and pelvic area are always covered with a pangi – a one piece wrap around cloth.

Ndyuka people of Suriname

Aukan men often go topless or wear the camissa (a toga-like cloth thrown over one shoulder and caught with a knot). There are times when Aukan men wear a mixture of traditional Aukan dress and Western dress (especially hats) to formal occasions. There is a trend toward the wearing of more Westernized clothing especially among the young.

NDYUKA WOMEN IN THEIR TRADITIONAL DRESS

Aukan Art

Aukaners enjoy producing art in a variety of ways, all of which are gender specific. Men make elaborate wood carvings including boat oars, trays, canoes, and houses. They frequently brightly paint the doors of their homes as well as their boat oars.

Men are considered to be the master artists of the Aukan people. Women, on the other hand, downplay their own artistic abilities. Women carve out calabash bowls, ladles, and containers. Women also sew and cross-stitch designs on their husbands’ camissa (a togatype of garment thrown over one shoulder and caught with a knot). The giving of artistic gifts having carefully been made are important expressions of love between spouses.

Ceremony

The biggest annual holiday in Aukan society is held to mark the end of the one year period of mourning (Bokode). Another holiday is celebrated in July to commemorate the end of slavery (Masipasi). Other celebrations center around cyclical family events. For example, women are required at each menstruation to be separated from the rest of society. Special menstrual huts are available for women to use during this time. When women return to their own homes following menstruation, there is a time of happy celebration. Also, three months after a woman gives birth, a woman and newborn are no longer believed to be ritually unclean and are released back into village life. A time of celebration and presentation of the infant ensues.

Source:https://www.oralitystrategies.org/files/1/312/Worldview%20of%20the%20Aukaners.pdf

http://mariekeheemskerk.org/Publications/Dissertation%20complete.pdf

Two young girls, "Kwei uman ', with babies on their sides. Next to them are two boys together. The two girls wear Kwei, a cloth that covered their genitals. Wearing a Kwei indicates that the girls are not yet mature. Between their 15th and 18th years were girls festively initiated into adult woman. Circa 1910

Dyuka people of Suriname

They are the descendants of African slaves brought over from Central and West Africa in the 17th and 18th centuries by the Dutch to work the many plantations in the coastal regions. Conditions on the plantations were often cruel and inhumane resulting in escapes of slaves into the jungle interior of the country where

they would not be followed. The Aukaners set up their own societies, forming a unique culture, language and lifestyle. For over 300 years the Aukaners have lived in relative isolation from the outside world. This paper will attempt to explore and document who the Aukaners are and provide at least an initial look into how they view the world.

Ndyuka woman and her baby girl

Classification/Name

Slaves who escaped from their captivity to form independent people groups are known as Maroons. There are two Maroon groups in Suriname: the Aukaners and the Saramacans. Aukaners go by two different names depending largely on the location in which they live. Those Aukaners who live along the Tapanahony River and make up the ethnographic core of the people group refer to themselves as Ndjuka. Aukaners who live in the city as well as the coastal Cottica River region refer to themselves simply as Aukaners.

Ndyuka tribes men of Suriname

While these two groups of individuals go by different names, they share the same cultural, historical and family background and see themselves as the same people group. There are two other related groups that speak a very similar dialect to Aukans: the Aluku, and the Paramacca. These two groups today are considered distinct. Of these the Aukan/ Ndjuka is the largest group, numbering approximately 33,000. In spite of the their common kinship and language, the Aukaner sub-groups are not friendly with each other and do not necessarily cooperate. Within the last few years, a large but undetermined number of Aukaners have migrated to French Guiana.

Ndyuka people

Language

Ndyuka also called Aukan, Okanisi, Ndyuka tongo, Aukaans, Businenge Tongo, Eastern Maroon Creole, or Nenge is a creole language of Suriname, spoken by the Ndyuka people. Most of the 25 to 30 thousand speakers live in the interior of the country, which is a part of the country covered with tropical rainforests. Ethnologue lists two related languages under the name Ndyuka.

Ndyuka is based on English vocabulary, with influence from African languages in its grammar and sounds. For example, the difference between na ("is") and ná ("isn't") is tone; words can start with consonants such as mb and ng, and some speakers use the consonants kp and gb. (For other Ndyuka speakers, these are pronounced kw and gw, respectively. For example, the word "to leave" is gwé or gbé, from English "go away".) There are also influences from Portuguese and other languages.

Slavery destroyed entire continent - On the hunt runaway slaves was opened with bloodhounds. Once caught, they could count on the death penalty. Following the English poem "The Dismal Swamp" by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Richard Ansdell painted in 1861 the hunted slave couple. - Photo National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside

Modern orthography differs from an older Dutch-based orthography in substituting u for oe and y for j. The digraphs ty and dy are pronounced somewhat like the English ch and j, respectively. Tone is infrequently written, though it is required for words such as ná ("isn't"). The Ndjuká syllabary was invented by Afaka Atumisi of eastern Suriname in 1910. Afaka claimed that he had a dream in which a spirit prophesied that a script would be revealed to him. He went on to invented the Ndjuká or Djuka script, which is also known as the Afaka script (afaka sikifi).

A Woman of Maroon Aukaanse (Ndyuka) descent. Her clothing consists of a pangi, worn to her waist and a cloth tied across her right shoulder.She also carries a number of rings above her ankle. Circa 1900

The Ndyuka language has three dialects: proper Ndyuka (or Okanisi), Aluku, and Paramaccan, which are ethnically distinct. Kwinti is distinct enough linguistically to be considered a separate language, though it too is sometimes included under the name Ndyuka.

Ndyuka was also a basis of the Ndyuka-Tiriyó Pidgin. Here is an example of Ndyuka text, and its translation into English (showing the similitarities as well as the lexical evolution), adapted from Languages of the Guianas (SIL Publications):

En so den be abaa na a líba, dísi wi kai Kawína Líba. Di den abaa de, den abaa teke gwe na opu fu Kawína. En so den be waka langa langa gwe te na Mama Ndyuka ede, pe wi kai Mama Ndyuka.

And so they crossed the river, which we call "Kawina [Commewijne] River". Having crossed it, they went way upstream along the Commewijne. Thus they walked a long, long way, clear to the upper Tapanahony, the place we call "Mama Ndyuka".

The language bears some similarity to Twi and other Akan languages spoken by the Akan people of Ghana.

Aukaners of Suriname

Brief History

The Aukaners were slaves who escaped from plantations on the coastal part of Suriname in the 1600’s and 1700’s. After their escape, these freed slaves would form clans, which are the building blocks of their society even today; villages were located in the jungle interior. In an effort to free other slaves, the Maroons frequently raided Dutch plantations resulting in loss of property and some loss of Dutch lives.

Ndyuka tribe woman with her baby. Circa 1952

A protracted guerilla war ensued ending only with a peace treat with the Dutch in 1760. The Aukaners were the first of the Maroon groups to be granted semi-independence as a result of this treaty. The Aukaners were free to live in isolation and received annual payments from the Dutch government to cease their raiding of Dutch plantations.

Ndyuka maroons of Suriname. Circa 1892

The Aukaner people remained relatively isolated until the 1950’s when the government in Paramaribo began to employ Ndjuka’s. This pace of migration continued in the 60’s and 70’s as tens of thousands of Surinamers moved to the Netherlands in the wake of Suriname independence in 1975. (About 1/3 of the Suriname population –200,000 people – migrated to the Netherlands.)

In 1986 a Civil War began in Suriname between the Maroons and the Dutch government. As a result many of those who had migrated to the capital returned home to renew their cultural ties and re-establish their loyalties. The war lasted until 1990 when a new peace treat was finally signed. It is important to note that the war was responsible for a renewed commitment to their own way of life and culture for the Aukaner people.

Even though today up to 50% of the population at some time or another lives in the capital (of these, 25% are permanent moves and 25% are temporary, employment moves), they still consider themselves solidly Aukaner and are proud of their history and heritage.

Aukan girl showing her tribal initiation marks on her belly. Circa 1919

The Ndjuka appear the most mobile and market-oriented of all Maroons. By the early 19th century, the Ndjuka had settled closer to the urban area, along the Cottica and Lower Saramaka Rivers. Ndjuka men marketed timber to Paramaribo customers and occasionally grew food for plantations along the coast and for Paramaribo (ThodenVanVelzen and VanWetering 1991). Since the 1960s many Ndjuka have moved to Paramaribo, primarily for economic reasons (Lamur 1965). Today, Maroons make up 4.6% of the larger Paramaribo area (Schalkwijk 1994: 22). Most urban Maroons seem to be of Ndjuka origin. If only half of the Maroons in Paramaribo are Ndjuka, then about 30% of the Ndjuka population live in the city today. The Ndjuka work more in mining than Maroons from other groups.

Late Paramount Chief of Ndyuka, Granman Matodja Gazon

Economy

Agriculture is the main focus of the Aukan economy. Items grown, however, are for the personal use of those who grow them (as well as a small group of related family members). There are no markets. The main crop is dry rice; other crops include cassava, taro, okra, maize, plantains, bananas, sugar cane and peanuts. Hunting and fishing are also significant contributors to the overall economy of the region. Again, game and fish are shared with a small group of kinsmen; none are purchased in a market-style economy.

Ndyuka tribe woman cultivating the land after burning

Also contributing to the Aukan economy today are items purchased in Paramaribo by Aukan men employed there. These items are then brought into the interior and include shotguns, tools, pots, cloth, hammocks, salt, soap, kerosene, rum, outboard motors, transistor radios, and tape recorders. Aukaners are also emplyoyed in the areas of forestry and gold mining. Gold mining is now employing many Aukaners , especially in the are of Sella Creek (a tributary of the Tapanahoni).

Ndyuka tribe boy holding plantain

The primary family unit in Aukan society is the matriclan (“lo”). Matriclans originated from a particular group of runaway slaves of a specific plantation from which they derived their names. There are twelve matriclans; each matriclan contains kinsmen who are matrilineally related. These are the strongest family ties; marriage is important but does not produce as vital a family link.

Each Aukan village contains three groups of people:

1.) matrilineal descendants of common ancestress (“people of the belly”)

2.) descendants of the men of the matrlineage (“fathers made them

children”)

3.) those who moved to these villages as relatives by marriage; i.e. affines(“those who have come to live”)

Ganman

Aukaners practice polygamy (more than one wife for a man) but only if the man can afford to maintain more than one household. About 1/3 of the marriages are polygamous. Marriage in the Aukan sense consists of an official meeting held of the woman’s matriclan resulting in a verbal contract. Basically, the woman agrees to bear the man’s children; the man agrees to provide materially for his wife.

Granman Matodja Gazon, the late Paramount Chief of the Ndyuka.

Once married couples must choose where they will live. Due to the fact that 1/3 of the men have more than one wife, care is taken in making that choice! In a recent study the following was discovered:

25% couples chose to live in the village of the husband’s family

30% couples chose to live in the village of the wife’s family

28% couples chose to live in both places

15% chose to live in their own villages with only brief visits to each other

It is not unusual for a man to own a house in his wife’s village, his lineage village and his father’s village. Divorce is relatively easy and frequent, some say as high as 40%. In order to obtain a divorce, the man informs his wife’s matriclan’s leaders that he no longer wants to be her husband. If the man has wronged the woman in some way, a fine is levied by the matriclan to appease the ancestral spirits. It is said that if a woman “overpowers” a man by her attitudes and actions that man should divorce his wife and go back to his own village

Aukaner woman with her stereo player

Neighbor/Village Relationships

There are many family groups within each village in Aukan society. Families relate to each other on a competitive basis. Limited resources, game, fish and planting grounds lead to a competitive agenda. Most family to family meetings take place to settle disputes between the families. Friendships are few outside of the family.

Aukan couple Circa 1910

Aukan society is egalitarian; no social classes exist for the most part. There are positions of respect, however. The hierarchy of respect for most Aukan villages is as follows: religious practitioner followed by gaanman followed by captains followed by basias followed by storeowners/teachers followed by matriclan leaders.

Aukaner selling stuffs at Paramaribo,Suriname

As can be seen, any white person or non-Aukaner is looked at with a certain level of distrust. Aukaners must always see themselves as being in the winning position when dealing with foreigners. They are very hesitant to reveal their true thoughts to foreigners, especially in the areas of religion and folk tales. This has obvious ramifications for the missionary, and every effort must be made to gain trust and acceptance.

Ndyuka tribe Maroons of Suriname oerforming their traditional dance

The Authority/Political Structure

There are four groups of authority in Aukan society: elders (including the paramount chieftain – the Gaanman); the captains (kabitens); kunu (avenging spirits of ancestors); and the priests (shamans, herbalists, funeral foremen, etc.). The elders make most of the decisions that are non-religious in nature in the society. Captains are local leaders; the primary captain (like a mayor in some sense) is called the Ede Kabiten. Each

captain as two male and two female assistants called basias. Male basias act as village criers, announcing the beginning of village functions as well as other news. Female basias cook and serve food for large village functions and maintain mortuary and other meeting places. In reality priests have the utmost authority in that they interpret the wishes of ancestral spirits and kunu. More detail on this will be provided in the section

on religion.

The principal political offices (Gaanman and kabitens) are determined through matrilineal lines. Successors of these offices are distant relatives (must belong to the next generation) of the preceding officer.

Beautiful painting of Aukaner people

Law and Order (Social control)

Religious taboos form the framework of law and order in the Aukan society. When a dispute arises among Aukaners, it is usually settled after an impasse is reached. Typically, there is much yelling and gesticulating. A mediator (who is usually an affine; i.e. one who has married into the family) is called in to keep grievance from escalating to the point of angering the matriclan’s ancestors.

Ndyuka people

In settling disputes, both sides must feel that they have achieved a cumulative gain in the decision-making process. The fear of kunu generally acts as a strong motivation to settle the dispute. If the kunu become angry, there will be sickness and/or death in some member of the village (not necessarily the disputing parties). As a result, it is in the best interest of the entire village to make sure that disputes are settled before matters escalate.

Physical abuse is uncommon; striking each other is a very strong taboo. The exception to this rule is a wife caught in adultery – in this instance the husband has the right to beat the wife within certain parameters. (He must not use a stick or other weapon; the fight cannot take place on river or in the fields.) Citizens in this case are expected to intervene and stop punishment (much like the intervention of adults in the discipline of

children). Unfortunately, in recent times there have been higher levels of physical abuse, perhaps resulting from the negative influence of gold miners in the area.If a member of a village refuses to settle a dispute, the common punishment is ostracism. It is important to realize, however, that the overarching theme of Aukan law is a pursuit of mercy over justice. If, however, the ancestral spirits demand justice, punishment is carried out swiftly out of fear.

Nduka people

Religious Structure

Religion plays an extremely important role in the life of the Aukaner. The religious structure is one of animism and ancestral spirit veneration. There is a three tiered hierarchy of gods which plays a crucial role in every aspect of Aukan life. Some of the most significant gods are now discussed. The creator, the god who is

most powerful, is called “masaa gadu.” One of the most powerful spirits is “father god” (“papa gadu”) which is an incarnation of the boa constrictor. This is a god of mayhem and evil and is invoked in witchcraft. Because Aukaners are polytheistic, they are often willing to add Jesus to their pantheon of gods, probably in the second tier.

Superstition plays a major role in the life of an Aukaner. Individuals live in fear that they will commit some sin that will upset their ancestral spirits. Avenging, ancestral spirits are called “kunu” and must be appeased (through libations and sacrifices) when a wrong is committed. All sickness (especially serious illness) is seen to be the result of kunu action. In sickness or death, the ritual of divining is undertaken to determine the

cause of the illness (i.e., who is to blame for the sickness by their sin). This is accomplished through the use of oracles (often hair of the deceased) tied in a bundle and attached to a long plank. Two men hold the plank on their heads and then questions are put to the oracle. The way the plank moves, answers the questions. Aukaners also use charms, amulets, and fetishes to protect them from evil. Witchcraft is a reality in the Aukan society and is to be feared. Priests make decisions on whether someone is a witch. Frequently, when someone dies of unknown reason, the priest will mark them as a witch.There is a definite sense of good and evil in the Aukan mind set. Evil is associated with great danger, so it is to be avoided as much as possible. When a sin is committed, atonement is made quickly as directed by religious practitioners (priests and

mediums). The concept of salvation by faith is foreign to Aukan thinking. There is the concept of mercy in their system of justice, but atonement must always be made to cover sin. Aukan mindset would be equivalent to a salvation by works. Converts to any religion (including Christianity) are seen as a definite threat to the Aukan way of life. Often, new converts move out of their houses into new homes away from the traditional

village. Aukaners will intially listen to converts and try to add this new belief into their own religious world view. Syncretism is a real possibility and steps must be taken to ensure that true Christianity is presented.

The Aukaner sees God as stern, far-removed and a deity to be feared. The belief is that God became disgusted with mankind (especially the Aukan people) and removed himself from their presence. Prayers center around pleas for mercy for any accidental sins they may have committed.

Religious leaders hold an important place in society and have a great amount of power. Often the spiritual leaders are chosen by the ghost of a deceased ancestor or one of the gods to be used as a medium. The individual will then become possessed to give a message to the matriclan. The more this individual is possessed, the more of a spiritual leader he becomes. Eventually, after years of serving his clan as a medium, the person will be elevated to the position of priest. It is significant to note here that men alone can be possessed by the most important spirits. Women do act as mediums of the snake gods.

Ancestral shrines are important to Aukan ritual life, and, in fact, must be present for a settlement to be a true Aukan village. The two ancestral shrines of most significance are the mortuary (“Kee Osu”) and the ancestor pole/flagpole (“Faakatiki”).As stated earlier, Aukaners are mistrustful of foreigners and resistant to true

Christianity. They are a strong-willed people who are very proud of their heritage. They are especially proud to be the descendants of runaway slaves whom they see as their brave and defiant ancestors. Acceptance of Christianity, in the Aukan mind, would involve turning away from their ancestors and rejecting their way of life. Pentecostal churches have made some breakthroughs in Aukan society. It is estimated that there are

about 3000 Aukan Christians, the majority of whom live in Paramaribo or the Cottica region. Worship is led in Sranan Tongo. There are very few Christians in the interior

Ndjuka God Pantheon

Three Tiers

I MASAA GADU - The Lord God

-The fountainhead of all Creation

FOR ALL HUMANKIND

II GAAN Gadu-Great God or OGII-Danger GEDEONSU-Protector

GAAN Tata-Great Father

-Defender against Ndjuka enemies -King of forest Sprits -Shielding,comforting deity

such as witches “Wisimen” -Ambivalent toward humans -Offers solace

-Led Ndjukas out of slavery -Very Destructive unless appeased -Medicine Men “Obiaman”

-Defends traditional values/culture

assoc. with this deity

(taboos & persecutes thieves, immoral)

THESE ARE TRIBAL / NATIONAL GODS OF AUKANERS

III Yooka Papa Gadu or Vadu Ampuka Kumanti

Ancestor Spirits Reptile Spirits Bush Spirits Celestial Spirits

Birds, thunder/lightning

Bakuu – Demon Spirits

Helpful then turn destructive

-Depicted as humans with special powers

-Control particular domains and have particular interests and frailties

-Are able to procreate

-Except for Kumanti, all can turn into Avenging Spirits (Kunu)

THESE ARE MINOR DEITIES OR INVADING SPIRITS

Religious Bridges

There are many bridges to the gospel in the Aukan religion. Bridges identified

thus far include the following:

Belief in mercy and merciful intervention

Belief that God is the creator

Belief in sin

Belief in sacrifice to make atonement

Concept of “You reap what you sow.”

Concept of ancestors – presenting Old Testament characters as ancestors of faith (one specific story – Joseph)

Belief in the after life

No trouble believing Jesus did miracles and was son of God

Belief in the spiritual world

These bridges can be used as points of agreement in sharing the Gospel of Jesus Christ .

Ndyuka women showing her back tribal beautification marks (Kamemba). Circa 1915

Dress

The Aukan people have a very typical style of dress which distinguishes them from Western society. Aukan women often go topless or wear a bra only. The upper thigh, buttocks and pelvic area are always covered with a pangi – a one piece wrap around cloth.

Ndyuka people of Suriname

Aukan men often go topless or wear the camissa (a toga-like cloth thrown over one shoulder and caught with a knot). There are times when Aukan men wear a mixture of traditional Aukan dress and Western dress (especially hats) to formal occasions. There is a trend toward the wearing of more Westernized clothing especially among the young.

NDYUKA WOMEN IN THEIR TRADITIONAL DRESS

Aukan Art

Aukaners enjoy producing art in a variety of ways, all of which are gender specific. Men make elaborate wood carvings including boat oars, trays, canoes, and houses. They frequently brightly paint the doors of their homes as well as their boat oars.

Abeng

Men are considered to be the master artists of the Aukan people. Women, on the other hand, downplay their own artistic abilities. Women carve out calabash bowls, ladles, and containers. Women also sew and cross-stitch designs on their husbands’ camissa (a togatype of garment thrown over one shoulder and caught with a knot). The giving of artistic gifts having carefully been made are important expressions of love between spouses.

Ceremony

The biggest annual holiday in Aukan society is held to mark the end of the one year period of mourning (Bokode). Another holiday is celebrated in July to commemorate the end of slavery (Masipasi). Other celebrations center around cyclical family events. For example, women are required at each menstruation to be separated from the rest of society. Special menstrual huts are available for women to use during this time. When women return to their own homes following menstruation, there is a time of happy celebration. Also, three months after a woman gives birth, a woman and newborn are no longer believed to be ritually unclean and are released back into village life. A time of celebration and presentation of the infant ensues.

Source:https://www.oralitystrategies.org/files/1/312/Worldview%20of%20the%20Aukaners.pdf

http://mariekeheemskerk.org/Publications/Dissertation%20complete.pdf

Two young girls, "Kwei uman ', with babies on their sides. Next to them are two boys together. The two girls wear Kwei, a cloth that covered their genitals. Wearing a Kwei indicates that the girls are not yet mature. Between their 15th and 18th years were girls festively initiated into adult woman. Circa 1910

Suriname Dyuka Maroons, a timber overturning. Circa 1925

Thousands pay final respects to Paramount Chief Matodja Gazon

Sources: De Ware Tijd, Starnieuws

Villagers of Drietabiki carry the coffin containing the body of the late granman Matodja Gazon for a last tour of his residence. Shortly after the tour, a fleet of ten boats escorted the coffin to the burial ground in Ma-Kownoe-Gron. (dWT photo/Gilliamo Orban)

On Tuesday 10 April 2012 thousands of people gathered in the Ndyuka village of Drietabiki in Suriname to pay their final respects to granman Matodja Gazon, the late Paramount Chief of the Ndyuka. The widely esteemed dignitary was buried at a reserved spot in Ma-Kownoe-Gron. This is an area downstream of the village of Poeketi, which is also close to Drietabiki – Gazon’s former residency.

The Paramount Chief of the Ndyuka, who was only recently crowned ‘king of the Ndyuka’ – in honor of his status and achievements – died on 1 December 2011 after suffering a stroke. He was 91.

Present at Drietabiki to bid him farewell were visitors from all over the country, as well as guests from abroad. The attendees included leaders and members of all six Maroon communities in Suriname, government officials and other special invitees.

The Ndyuka nation organized the ceremonies, while the government of Suriname contributed financially. The funeral took place at a relatively late date, about a month after the traditional period of three months post-death. The cause of this delay was a late start of the construction work at the grave site, as well as an accident. In February of this year, part of the dugout grave collapsed, causing one of the diggers to break his leg. Upon this, labor at the site was temporarily suspended.

The Ndyuka nation organized the ceremonies, while the government of Suriname contributed financially. The funeral took place at a relatively late date, about a month after the traditional period of three months post-death. The cause of this delay was a late start of the construction work at the grave site, as well as an accident. In February of this year, part of the dugout grave collapsed, causing one of the diggers to break his leg. Upon this, labor at the site was temporarily suspended.

The grave of the late Ndyuka-leader is not an ordinary one, nor is his coffin. Both are grand, thereby underscoring the status of the deceased among his people. Labor at the grave site was conducted by sixty diggers who worked in daily teams of six. The end result is a massive vault that sits at 20 square meters at a depth of 7 meters. Of likewise impressive proportions is the coffin, which measures 3 meters long, 1.5 meters wide and 1.5 meters high.

Explaining the unusual sizes of the grave and coffin, Ndyuka captain Johan Djani commented in newspaper De Ware Tijd, “The grave is like a house. It holds not only the coffin, placed on a traditional bench, but also personal belongings of the deceased and gifts to aid him on his final journey.”

In another article by the same newspaper, anthropologist Salomon Emanuels sheds light on the origin of the customary three-month-waiting period before the burial of a Maroon Paramount Chief. Says Emanuels, “This tradition started in colonial times. By the peace treaty of 10 October 1760 the Maroons were obligated to report the death of a Paramount Chief to the governor. But in those times, the Maroons had to paddle their way down, so a trip to Paramaribo took at least three weeks. Once in Paramaribo, they had to wait for about another week before the governor could see them, and afterward they had to travel all the way back, upon which the necessary rituals could start. This whole process took a good three months. Hence the three-months tradition.”

Villagers of Dritabiki carry the coffin containing the body of the late granman Matodja Gazon for a last tour of his residence. Shortly after the tour, a fleet of ten boats escorted the coffin to the burial ground in Ma-Kownoe-Gron. (dWT photo/Gilliamo Orban)

The Ndyuka funeral priest (oloman) and his team in February of this year, preparing for the funeral proceedings (photo from Starnieuws, taken by the Suriname government)

The Ndyuka funeral priest (oloman) and his team in February of this year, preparing for the funeral proceedings (photo from Starnieuws, taken by the Suriname government)

The late Paramount Chief of the Ndyuka has lain in state in Drietabiki for the full duration of the funeral preparations. A funeral priest was in charge of these preparations. He performed libations, for example, and consulted an oracle on a daily basis to receive advice on key matters, such as choosing a funeral date.

Meanwhile, representatives of the 12 Ndyuka clans conducted mourning ceremonies in various places, both within Suriname as well as in the Netherlands. These ceremonies will continue in months to come. The Ndyuka nation closes the period of mourning no sooner than one year after a funeral.

The duties of the Paramount Chief are currently performed by lower ranked dignitaries (such as captains or ‘kabitens’) of various Ndyuka clans. The identity of Matodja Gazon’s successor, who will be appointed and installed after the one year mourning period, has yet to be publicly announced. According to tradition, this person will come from the ranks of the Otoo-clan, as Matodja Gazon himself was.

Magaretha Malontie, district commissioner for the region Tapanahony has said in an interview with De Ware Tijd that the name of the successor is kept confidential for the time being, ‘as a sign of respect for the late granman’. De Ware Tijd writes on stating, “Yet some, including village elders, already know who the successor is. Gazon had chosen a candidate before his death. An oracle has indicated this person. During the ‘purblaka’ -ritual (literally ‘remove the darkness’) that marks the end of the mourning period, the successor’s name will be disclosed to the public. The date for the ‘purblaka’ will be set in the near future.”

Samuel Forster new paramount chief to Paramaccans

Sixty year old Samuel Samapima Forster has taken the oath of office as Paramount Chief for the Paramaccan Maroons in Suriname. The official ceremony took place on Saturday February 27th at the Presidential Palace in the capital city of Paramaribo. Suriname’s president Ronald Venetiaan was present , as were Secretary of Regional Development Michel Felisi and District Counselor Raymond Landbrug.

Forster is to hold residency at Langatabiki, from where he will preside over ten villages along the River Marowijne. The Paramaccan people comprise approximately two and a half thousand individuals, the majority of whom live in Suriname, while about five hundred live in French-Guyana.

Samuel Samapima Forster, father of fourteen children, is a nephew of former chief Jan Levie and is also known by his unofficial name of Samuel Johannes Amoida.

The new chief is congratulated by secretary Michel Felisi of Regional Development. (dWTphoto / Paul San)

SEO services in Amsterdam Netherlands

ReplyDeleteHi, Are you familiar with any persons who make the Pangi fabric in Suriname?

ReplyDeleteThank you